Literature and its Effect on the Harlem Renaissance

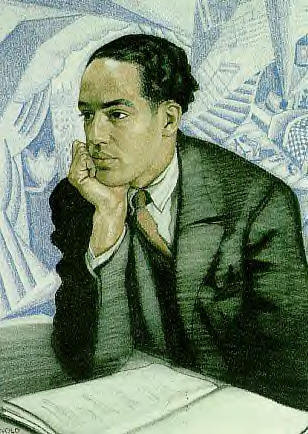

Langston Hughes: Poet Laureate of the Harlem Renaissance

Analysis of The Negro Speaks of Rivers, by Langston Hughes

Literature and its Effect on the Harlem Renaissance

Never before had African American authors been given a stronger voice that would reach the far corners of the world as they did during the 1920s Harlem Renaissance. After hundreds of years of being cast aside and ignored by the rest of western white society, talented black writers and poets were given an outlet and an audience for their creative impulses. The works of these bright young literary minds helped to fuel a movement that empowered a generation of Negro artists and exalted them and the image of the African American to new heights and a new level of respectability.

In

the early years of the Roaring Twenties, the publication of three works signaled

the new creative force that had come to exist in African American literature. In

1922 the black writer Claude McKay’s Harlem Shadows, a collection of

poetry expressing the both the sophistication and the dark side of the Harlem lifestyle, became one of the first books to be printed by a mainstream national

publisher, Harcourt Bruce and Company (Lewis 24). Jean Toomer’s experimental

novel that utilized both prose and poetry in portraying American black life in

the urban North and rural South, Cane, was published the following year. There

Is Confusion, the first novel written by editor Jessie Fauset, illustrated

African American middle-class life from a woman’s point of view in 1924 (Lewis

25). These three books, particularly the last, demonstrated that the opinions of

African Americans did begin to have importance among

the intellectuals of

the

world, and their thoughts would not be so quickly cast aside as blacks began to

empower themselves both emotionally and creatively; instead of African American

intellectuals modeling themselves after the prestigious white academics, they

began to define their own identities within their own ethnicity, and spawn a cultural revolution that would celebrate the strength and beauty of African

roots instead of masking them in shame (Singer 75). With these early works

laying the groundwork, the Harlem Renaissance was set off between the years 1924

and 1926 (Lewis 25).

lifestyle, became one of the first books to be printed by a mainstream national

publisher, Harcourt Bruce and Company (Lewis 24). Jean Toomer’s experimental

novel that utilized both prose and poetry in portraying American black life in

the urban North and rural South, Cane, was published the following year. There

Is Confusion, the first novel written by editor Jessie Fauset, illustrated

African American middle-class life from a woman’s point of view in 1924 (Lewis

25). These three books, particularly the last, demonstrated that the opinions of

African Americans did begin to have importance among

the intellectuals of

the

world, and their thoughts would not be so quickly cast aside as blacks began to

empower themselves both emotionally and creatively; instead of African American

intellectuals modeling themselves after the prestigious white academics, they

began to define their own identities within their own ethnicity, and spawn a cultural revolution that would celebrate the strength and beauty of African

roots instead of masking them in shame (Singer 75). With these early works

laying the groundwork, the Harlem Renaissance was set off between the years 1924

and 1926 (Lewis 25).

Claude McKay

The

National Urban League was founded in 1910 with the goal of lending a hand to

help blacks face the economic and social issues they faced as they migrated to

the urban North. On March 21, 1924, its head Charles S. Johnson held a dinner

dedicated acknowledge the new African American literary talent in the country

and to introduce them to New York’s upper-crust white literary  establishment.

Society took a new interest in these new voices in American literature, and soon

after,The Survey Graphic, a socially concerned publication that involved

itself in the study of cultural pluralism released an issue that studied the new

ethnic phenomena that was occurring in New York’s Harlem (Lewis 25). The issue

highlighted works by African American authors and devoted itself to explicating

the aesthetic of the new black writing and art. White author Carl Van Vechten

was fascinated by this submergence and explosion of the black lifestyle and

exposed Harlem life to the nation in his book, Nigger Heaven, in 1926.

Its portrayal of the rich and poor sides of Harlem generated a “Negro vogue”

that attracted thousands of urbane black and white New Yorkers there to witness

its glamorous and stirring nightlife and fueled a nationwide market for African

American art and literature (Lewis 26). This interest in African American works gave black artists and writers room to spread their creative wings and fashion

from their life experiences and their distinct views some of the most individual

and imaginative literary works and art pieces the world had ever seen. With the

publication of the all-black magazine Fire!! in the fall of 1926 young

black artists like Wallace Thurman, Zora Neale Hurston, and Langston Hughes

seized the Harlem Renaissance by the reigns and made it their own. There was no

single literary style or political theory that clearly characterized the

Renaissance; what united the authors of the time period was their drive to

participate in a collective attempt and dedication to allowing the vent and door

of creative expression to the black experience. Concentration on the life

experiences of blacks in Africa and the American South, a powerful sense of

cultural dignity, and a drive for political and social unity harmony were

widespread themes that ran through the art of African American poets and authors

throughout the Harlem Renaissance (Lewis 27). The most distinguished feature of

the literary movement was the diversity and wide range of its expression.

Sixteen African American authors released over fifty collections and novels of

fiction and poetry as dozens more black artists left lasting marks on the worlds

of theater, music, and art between the mid-1920s and 1930s (Lewis 28) .

establishment.

Society took a new interest in these new voices in American literature, and soon

after,The Survey Graphic, a socially concerned publication that involved

itself in the study of cultural pluralism released an issue that studied the new

ethnic phenomena that was occurring in New York’s Harlem (Lewis 25). The issue

highlighted works by African American authors and devoted itself to explicating

the aesthetic of the new black writing and art. White author Carl Van Vechten

was fascinated by this submergence and explosion of the black lifestyle and

exposed Harlem life to the nation in his book, Nigger Heaven, in 1926.

Its portrayal of the rich and poor sides of Harlem generated a “Negro vogue”

that attracted thousands of urbane black and white New Yorkers there to witness

its glamorous and stirring nightlife and fueled a nationwide market for African

American art and literature (Lewis 26). This interest in African American works gave black artists and writers room to spread their creative wings and fashion

from their life experiences and their distinct views some of the most individual

and imaginative literary works and art pieces the world had ever seen. With the

publication of the all-black magazine Fire!! in the fall of 1926 young

black artists like Wallace Thurman, Zora Neale Hurston, and Langston Hughes

seized the Harlem Renaissance by the reigns and made it their own. There was no

single literary style or political theory that clearly characterized the

Renaissance; what united the authors of the time period was their drive to

participate in a collective attempt and dedication to allowing the vent and door

of creative expression to the black experience. Concentration on the life

experiences of blacks in Africa and the American South, a powerful sense of

cultural dignity, and a drive for political and social unity harmony were

widespread themes that ran through the art of African American poets and authors

throughout the Harlem Renaissance (Lewis 27). The most distinguished feature of

the literary movement was the diversity and wide range of its expression.

Sixteen African American authors released over fifty collections and novels of

fiction and poetry as dozens more black artists left lasting marks on the worlds

of theater, music, and art between the mid-1920s and 1930s (Lewis 28) .

The

Harlem Renaissance’s varied literary expression stretched far and wide, and

the interpretation of its prin- ciples ranged broadly. Claude McKay,

with others like Countee Cullen,

dealt with African American issues in classic forms, who used the traditional

English sonnet as a means for the structure of his passionate poem assailing

racist cruelty, "If We Must Die," in 1919. Langston Hughes, poet laureate of the Harlem Renaissance, took a

different approach, and instead chose a more modern medium linked directly with

his own culture; he interlaced the cadence and rhythms of black music into his

poems about African American life into his poetry, as he did in his collection The

Weary Blues in 1926 (Lewis 29). The Harlem Renaissance was fueled by the

literary developments in African American works that had a new emphasis on

rejecting the belief that complete assimilation into white society was the

answer to the black community’s identity issues and instead turning the path of discovery inward and celebrating the black way of life (Singer 75).

The literature of the Harlem Renaissance defined the emotions

and pride in their race that replaced African American’s once overwhelming

shame of it. In Harlem’s innovative and imaginative environment, painters,

writers, artists, musicians, and poets exchanged and fused creative theory in

cafes and parties, and the arts of all forms were interspersed to create and

make evident to the world the awe-inspiring ingenuity and beauty of the African

American spirit.

McKay,

with others like Countee Cullen,

dealt with African American issues in classic forms, who used the traditional

English sonnet as a means for the structure of his passionate poem assailing

racist cruelty, "If We Must Die," in 1919. Langston Hughes, poet laureate of the Harlem Renaissance, took a

different approach, and instead chose a more modern medium linked directly with

his own culture; he interlaced the cadence and rhythms of black music into his

poems about African American life into his poetry, as he did in his collection The

Weary Blues in 1926 (Lewis 29). The Harlem Renaissance was fueled by the

literary developments in African American works that had a new emphasis on

rejecting the belief that complete assimilation into white society was the

answer to the black community’s identity issues and instead turning the path of discovery inward and celebrating the black way of life (Singer 75).

The literature of the Harlem Renaissance defined the emotions

and pride in their race that replaced African American’s once overwhelming

shame of it. In Harlem’s innovative and imaginative environment, painters,

writers, artists, musicians, and poets exchanged and fused creative theory in

cafes and parties, and the arts of all forms were interspersed to create and

make evident to the world the awe-inspiring ingenuity and beauty of the African

American spirit.

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

Poet Laureate of the Harlem Renaissance

Langston Hughes is considered to be one of the most gifted African American writers of the twentieth century, and a man who was at the vanguard of the corps of the poets of the Harlem Renaissance who altered society’s view of the black community forever. Hughes was born on February 1, 1902 in Joplin Missouri, son to James Nathaniel and Carrie Hughes (Haskin 124). His parents separated when he was a child.

Langston Hughes spent much of his childhood living between his mother, who moved often to find work, and in Lawrence, Kansas with his grandmother, Mary Langston, a widow with an extraordinary life who imparted upon Langston a strong sense of cultural pride in their African American roots. She immersed her grandson in knowledge of African American history, telling him great epics of black heroes and reading him works by famous African Americans like W.E.B Dubois and Paul Lawrence Bunbar, and instilled in him a passion for literature that would shape the course of his life forever (Hill 18). He was never ashamed of his race, like many of his black peers who went mixed schools of both African American and white students; in the seventh grade, Langston was placed in a class in which the teacher segregated the black students into their own row at the far side of the room. Langston was quick to respond and put up a sign on each of the desks that read “Jim Crow Row;” school officials quickly put the racial separation between the students to an end (Hill 21).

After his grandmother died, Langston went to live with his mother in Cleveland, Ohio with her new husband Homer Clark. He attended Central High School there, where he was very well liked and was one of the most popular students in his class. He ran track and wrote poems for the school newspaper, and his love for writing grew; by the end of his junior year he had indefinitely decided that he would dedicate himself to becoming a writer (Haskins 126). At the end of his high school career he spent a year living with his father James in Mexico; through their personal relationship did not flourish, James Hughes was willing to pay for Langston’s education at Columbia University in New York City in 1921(Hill 32). Though Langston was thrilled to be living so close to Harlem, the center for African-American culture at the time, and made the most of it, he suffered much racial discrimination at Columbia, where few students befriended him and his professors snubbed him because of his color. He decided that he would leave Columbia and travel the world to learn more about the life and culture of African Americans (Hill 35). It was around this time that his poetry began to be published in the most famous African American newsletter, The Crisis, which soon began to have some of his work in every published edition (Haskins 128).

Langston

Hughes journeyed across the globe, taking odd jobs as a seaman and a crew member

of a number of world-traveling ships for two years. He wrote throughout this

time period, moved by experiences he had in Africa and around the world (Haskins

129). By the time he got back to the States the Harlem Renaissance was well

underway, and he was surprised to learn that he had become famous for his

published literary works in the intellectual black underground. The

African-American editor of the magazine Opportunity, Charles S. Johnson,

believed that Hughes more than any other black writer “completely symbolized

the new emancipation of the Negro mind” (Hill 44). Hughes proclaimed in a

well-known essay he called “The Negro and the Racial Mountain” that the

problem with African American intellectuals was that they would rather deny

their own race and be accepted by white society than embrace their roots and

accept themselves, and this stopped them from creating truly Negro art. Hughes

exemplified the true message of the Harlem Renaissance, which was to celebrate

the African-American culture. He stated that “We younger Negro artists who

create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or

shame” (qtd. in Hill 51). He shook off the drive that moved the middle-class

African American to desire to be white, and rejoiced in the acknowledgement of

the African American voice in a once-completely white dominated culture (Hill

52). His first book of poetry, The Weary Blues, was published nationwide

in 1926, and won him much critical acclaim from both the black and white

literary worlds. He was able to complete his college education at Lincoln

University in Oxford Pennsylvania (Haskins 130).

Langston

Hughes journeyed across the globe, taking odd jobs as a seaman and a crew member

of a number of world-traveling ships for two years. He wrote throughout this

time period, moved by experiences he had in Africa and around the world (Haskins

129). By the time he got back to the States the Harlem Renaissance was well

underway, and he was surprised to learn that he had become famous for his

published literary works in the intellectual black underground. The

African-American editor of the magazine Opportunity, Charles S. Johnson,

believed that Hughes more than any other black writer “completely symbolized

the new emancipation of the Negro mind” (Hill 44). Hughes proclaimed in a

well-known essay he called “The Negro and the Racial Mountain” that the

problem with African American intellectuals was that they would rather deny

their own race and be accepted by white society than embrace their roots and

accept themselves, and this stopped them from creating truly Negro art. Hughes

exemplified the true message of the Harlem Renaissance, which was to celebrate

the African-American culture. He stated that “We younger Negro artists who

create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or

shame” (qtd. in Hill 51). He shook off the drive that moved the middle-class

African American to desire to be white, and rejoiced in the acknowledgement of

the African American voice in a once-completely white dominated culture (Hill

52). His first book of poetry, The Weary Blues, was published nationwide

in 1926, and won him much critical acclaim from both the black and white

literary worlds. He was able to complete his college education at Lincoln

University in Oxford Pennsylvania (Haskins 130).

From this point forward, Langston Hughes made his living completely from his writing and publications. Many of his works in the late 1920s were written almost completely in the style of the blues, utilizing the everyday black vernacular and changing it from prose to pure and soulful poetry (Haskins 130). He portrayed African American life in America with colloquial realism in a sort of autobiographical novel, Not Without Laughter, which won him the Harmon Gold Metal for literature ( Howes 60). He wrote a collection of poems for young children called The Dream Keeper, which came out in 1932. He published The Ways of White Folks in 1934, a collection of short stories, which was adapted into Mulatto the next year, the longest-running play by an African-American writer on Broadway until the 1950s (Haskins 131). Hughes created his own drama group, the Suitcase Theater, in January of 1938. His mother passed away from breast cancer in 1939, and left him without emotional restraint to write a true autobiography called The Big Sea, which was published with much critical acclaim (Hill 69). Langston traveled across the country, lecturing and teaching in African American schools, helping students of all ages develop promising literary abilities and encouraging them to write. He never married or had children, but had two failed love affairs with two women, Anne-Marie Coussey and Sylvia Chen; he, however, never publicly displayed any sadness about this, and instead embraced his close friends as family (Haskins 133).

Throughout

the 1940’s Langston Hughes wrote radio scripts, lyrics for songs, and

especially, recurring columns for national newspapers. In 1943 he was writing a

weekly article in the most well known African American in the country, the

Chicago Defender (Hill 87). He wrote the column as an everyday barstool

dialogue between a somewhat bombastic narrator and his “simple-minded”

friend, Jesse B. Semple that observed the current political and racial scene in

a satirical fashion. Hughes was highly praised for this and likened to the

timeless American satirists Mark Twain, making him one of the most prominent

spokesmen on racial issues (Hill 88).

(Hill 87). He wrote the column as an everyday barstool

dialogue between a somewhat bombastic narrator and his “simple-minded”

friend, Jesse B. Semple that observed the current political and racial scene in

a satirical fashion. Hughes was highly praised for this and likened to the

timeless American satirists Mark Twain, making him one of the most prominent

spokesmen on racial issues (Hill 88).

In the 1950’s and 1960’s, Langston Hughes’s works reached some of their all-time highs. His poetry collection Montage of a Dream Deferred was published as a book in 1951, and featured one of his most famous poems, “Harlem,” which is more commonly known as “Dream Deferred” (Haskins 134). Hughes was a prominent figure in the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement; he had met Martin Luther King, Jr. on several occasions and greatly admitted him, and could never tolerate any criticism leveled at King (Hill 93). He spoke out against segregation, and contributed to the publication of one of the first books on Negro folklore and African American history books for children (Haskins 134). In 1961 he was the second African American after W.E.B Du Bois to be inducted into the National Institute of Arts and Letters, which was an association of the most well accomplished Americans in the fields of art and literature (Hill 104). After an incredible lifetime, full of personal and public triumphs, and changing the world’s view of the African American community, Langston Hughes passed away on May 22, 1967, at the age of 65 (Hill 113).

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

by Langston Hughes

I've

known rivers:

I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow

of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I

bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I

looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went

down to New Orleans, and I've

seen its muddy bosom turn

all golden in the sunset.

I've

known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers. Hear It! At Poets.Org

The

poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” was written in the summer of 1920; its

author, Langston Hughes, was only eighteen years old at the time (Hill 31). This

poem was his first ever published and became one of his most famous. “The

Negro Speaks of Rivers” clearly demonstrates the attitude of African Americans

during the Harlem Renaissance, and depicts the newly found pride of self in

black history and culture.

Like

so many other poems, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” has a message, and it

begins with its title. It is a Negro who speaks; not a prolific esteemed white

man, but a Negro, and a Negro of great importance, because it is ‘The’ Negro

who speaks. The speaker in the poem conveys his ideas in free verse, without

rhyme scheme, without inflated language, and no elaborate structure. Hughes, by

choosing not to utilize traditional syntactical devices demonstrates that he

will speak in the language of the people, one that is clear and undisturbed by

pomp and ostentation. The Negro speaks in a voice that is majestic without being

haughty; as one reads this poem, he is reminded of a soft speaking

African-American voice and the old Negro spirituals sung by the slaves. This is

achieved through the repetition of important phrases in the poem that require

particular emphasis and convey the speaker’s thoughts. The first line of the

poem, “I’ve seen rivers,” is repeated in the second line, and then

elaborated upon. This happens again in the eleventh and twelfth lines, and this

style is very similar to the style of songs sung by the African American slaves,

working in the fields or calming their children to sleep.

The voice is given greater magnificence, not only through how he speaks, but what he speaks as well. In the first stanza, the reader learns that the voice is an ancient and undying one, and has existed since the birth of man. There is a space indent in the third line to emphasize this point with the phrasing “human blood in human veins”(line 3). This shows that the voice of the Negro has always existed, and because of this has attained wisdom and is due much reverence. This phrasing gives African Americans reading this a sense of self-awe, and gives them what white western society had never afforded them – pride in their heritage. The next sentence, “My soul has grown deep like the rivers” (line 4) has a section all on its own to demonstrate its incredible importance. The soul of the Negro speaker is as deep as the rivers are, and the voice speaks for the universal soul of every African-American throughout the world. The river is a symbol of life and power. It contains what is necessary to satisfy thirst and hunger, the sustenance of the human body, and if the African American soul is as deep as the rivers, then the Negro soul has grown full enough to be self-sufficient, and complete itself. This simple phrase speaks volumes in eight words. In this poem it embodies an idea that helped to motivate the Harlem Renaissance, an idea which states that African Americans are beautiful, and do not have to assimilate into white society to be complete because through their own identity and their heritage they are complete unto themselves.

With

the fifth line in the poem, the speaker’s voice resonates with power and

self-possession. One can notice that besides the sentences that state “My soul

has grown deep like the rivers,” every sentence in the poem begins with

‘I,’ followed by an active verb. This demonstrates that the speaker seems to

proclaim that which he has experienced with honor, and pride. This furthers the

sense of dignity that Hughes is trying to give to every African American reading

this poem. Everything the voice experienced is depicted with grandeur and glory.

He states that he has “bathed in the Euphrates when the dawns were young”

(line 5). Laura Grimes states in her online article “The Cosmic Speaker in

‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers’” that the Euphrates is a river in the region

of Mesopotamia, which is known as the cradle of civilization. By saying that he

was present at that time, the voice conveys that it was not only the white man

that developed civilization, but the black culture as well (1). The next line,

“ I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep,” likens the

speaker to the African experience, and conveys that the natural world itself is

tied to the Negro soul.

With

the fifth line in the poem, the speaker’s voice resonates with power and

self-possession. One can notice that besides the sentences that state “My soul

has grown deep like the rivers,” every sentence in the poem begins with

‘I,’ followed by an active verb. This demonstrates that the speaker seems to

proclaim that which he has experienced with honor, and pride. This furthers the

sense of dignity that Hughes is trying to give to every African American reading

this poem. Everything the voice experienced is depicted with grandeur and glory.

He states that he has “bathed in the Euphrates when the dawns were young”

(line 5). Laura Grimes states in her online article “The Cosmic Speaker in

‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers’” that the Euphrates is a river in the region

of Mesopotamia, which is known as the cradle of civilization. By saying that he

was present at that time, the voice conveys that it was not only the white man

that developed civilization, but the black culture as well (1). The next line,

“ I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep,” likens the

speaker to the African experience, and conveys that the natural world itself is

tied to the Negro soul.

The next section is divided into another stanza, but continues the building idea in its first line. The fifth and sixth lines dealt with the speaker being independent from civilization, and the stanza after it dealt with the Negro’s interaction with the more modern civilization. The building motif is continued to demonstrate that the Negro built his own hut, and then he helped to build the immortal pyramids. This line achieves two things. It furthers the idea that people of color had just as much of a hand in developing civilization as the white man did. This shows that as Western white society in the United States continued to see the black race as beneath them, they had forgotten that they had accomplished great feats together, and blacks should not be denied their integrity because they were as strong and as intelligent as whites were. Another thing that this line achieves is that it shows that building of huts and pyramids is much like building heritage, and that the Negro built his culture and his heritage with his own hands, and his experiences were the fruit of his own labor. Building for oneself has the connotation of independence, and this showed that the 1920s were a time when the Negro was beginning to develop his own independent intellectual and creative identity in American society for the first time in history. The eighth line in the poem calls forth the idea of the emancipation of the slaves during Abraham Lincoln’s presidency. The speaker does not refer to their enslavement, only to their freedom. This also refers to the African Americans’ connection with nature as the river itself sang when the man who helped bring blacks their freedom journeyed to the south. The reference to black liberation is again testament to the strength and glory that the Negro spirit has experienced throughout his lifetime. The speaker continues to speak in informal language, calling Abraham Lincoln ‘Abe,’ and saying that he had seen the Mississippi’s ‘muddy bosom / turn all golden in the sunset’ (lines 8-9). This last piece can be interpreted, through the idea that the river is a symbol of the Negro soul, that though once his spirit was ‘muddy,’ cloudy, confused and opaque, experience and time brought it to a ‘golden,’ strong, and beautiful state at day’s end.

The

last line of the poem is a repetition of the fourth line, again stating, “My

soul has grown deep like the rivers.” This puts an emphasis on this statement

that is doubled by its isolation from the last stanza, and reiterates the idea

that because of their culture the African American soul is independently and

distinctively beautiful. The speaker has added to the meaning of this statement;

knowing what the speaker has experienced to make the soul deep is what adds

another dimension to the phrase. The speaker’s soul has grown to be rich and

complete because of the experiences he has had, not in spite of them. This poem

turned the belief that African Americans should be ashamed of who they were on

its heels, pushed it into a hole in the ground, filled it up, and danced on the

grave of it. The black identity was and still is something that transcends

societal restrictions, something strong and undying in the face of incredible

odds, and, most importantly, something to revel in, and this was the theme of

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” and of the Harlem Renaissance as well.

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

Haskins, Jim. The Harlem Renaissance. Brookfield, Connecticut: Millbrook Press, Inc., 1941.

Hill, Christine M. Langston Hughes: Poet of the Harlem Renaissance. Springfield, NJ: Enslow Publishers,

Inc., 1997.

Howes, Kelly King. Harlem Renaissance. New York: UXL Inc, 2001.

Grimes,

Laura. “The Cosmic Speaker in Langston Hughes' ‘The Negro Speaks of

Rivers.’” Classic

Poetry

Nov. 2002. Online. Internet. 16 Jan 2003.

Lewis, David Levering. When Harlem Was In Vogue. New York: Vintage Books, 1982.

Singer, Mark D. Literary Movements of the Twentieth Century. Los Angeles: Random House, 1989.

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*