-Countee Cullen,

from Yet Do I

Marvel

-Countee Cullen,

from Yet Do I

MarvelHow Literature Affected the Harlem Renaissance Biography and Influence of Countee Cullen Analysis of "Any Human to Another" Works Cited

Countee Cullen and Literature

of the Harlem Renaissance

Yet Do I Marvel At This Curious Thing:

To Make A Poet Black And Bid Him Sing !

-Countee Cullen,

from Yet Do I

Marvel

-Countee Cullen,

from Yet Do I

Marvel

How Literature Affected the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance introduced America to new forms of almost every kind of artistic expression. African-Americans were now being encourage, primarily by their own community, to celebrate their heritage and beauty through literature in a way that had not been previously achieved; to truly have a style of writing that was wholly their own. Through literature, blacks would encompass the characteristics of "The New Negro": pride in African culture, unique beauty, and a willingness to fight back against an oppressive society.

-----------------------------------------------------------

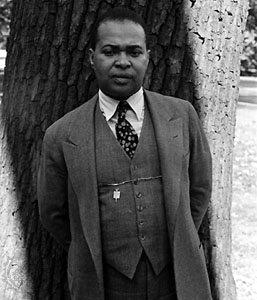

Three works published in the early

1920's marked the advent of the new Negro's literary voice. Claude Mckay's

Harlem Shadows, a volume of cultured poetry published in 1922, was one of the

first black works to be printed by the large-scale, national publisher Harcourt,

Brace, and Company. This milestone not only encouraged other publishers to

consider Negro literature for widespread publication, but also gave support to

those who wished to see black music and art uncovered and made public for the

nation to experience (Lewis 25). Consisting of short stories, poems, and a short

novel, Jean Toomer's Cane, pub

one of the

first black works to be printed by the large-scale, national publisher Harcourt,

Brace, and Company. This milestone not only encouraged other publishers to

consider Negro literature for widespread publication, but also gave support to

those who wished to see black music and art uncovered and made public for the

nation to experience (Lewis 25). Consisting of short stories, poems, and a short

novel, Jean Toomer's Cane, pub lished in 1923, compared and contrasted through

documentation the lives of southern, rural blacks with those of the urban north.

The book exposed the egregious racism that festered in both regions and

demonstrated the literary range and brilliance little believed blacks were

capable of. A year later in 1924, writer and editor Jessie Fauset wrote her

first novel, There Is Confusion, portraying the lives of middle-class

African-Americans. However, America now was made to view Negro life through the

eyes of the most vulnerable individual of the 1920's and 1930's, the black

woman. The ability and more so the genius of this fresh literature solidified

the movement as lasting and spurred further events that more overtly commenced

the Harlem Renaissance.

lished in 1923, compared and contrasted through

documentation the lives of southern, rural blacks with those of the urban north.

The book exposed the egregious racism that festered in both regions and

demonstrated the literary range and brilliance little believed blacks were

capable of. A year later in 1924, writer and editor Jessie Fauset wrote her

first novel, There Is Confusion, portraying the lives of middle-class

African-Americans. However, America now was made to view Negro life through the

eyes of the most vulnerable individual of the 1920's and 1930's, the black

woman. The ability and more so the genius of this fresh literature solidified

the movement as lasting and spurred further events that more overtly commenced

the Harlem Renaissance.

The events that helped the Harlem

Renaissance's influence spread and augment were interconnected and momentous. In

March of 1924, Charles S. Johnson, a high-ranking official in the National Urban

League, hosted a formal dinner in recognition of the new, blossoming literary

talent of the black community; the night was also an endeavor to acquaint New

York's established white literary enterprise with the rising black  writers. The

night proved successful and soon the societal-probing and criticizing magazine

The Survey Graphic released an entire issue devoted to Harlem the following

March. The black philosopher and academic Alain Leroy Locke edited the issue in

which a multitude of Negroes contributed work and the aesthetics of black

literature and art were defined.

writers. The

night proved successful and soon the societal-probing and criticizing magazine

The Survey Graphic released an entire issue devoted to Harlem the following

March. The black philosopher and academic Alain Leroy Locke edited the issue in

which a multitude of Negroes contributed work and the aesthetics of black

literature and art were defined. Carl Van Vechten's

Nigger Heaven was published

in 1926 and despite offending a number of blacks it did reveal an accurate

representation of life in Harlem; a "Negro vogue" was established

through the book's exposure of both the privileged and abject aspects of Harlem

and attracted large numbers of both the white and black erudite populations. The

buzz surrounding Harlem fueled a national market for black literature and in the

latter of 1926 Fire!!, the first solely-black produced magazine, introduced such

aspiring writers as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. There was no single

and defined style or ideology that could represent the gamut of artistic

expression of the magazine and the era, but an acute interest in the

African-American heritage, a sense of newly discovered racial pride, and the

yearning for social and political equality were fundamental to both (Lewis 27).

The magazine helped spur the over fifty volumes of poetry and fiction published

by more than 16 black writers from the mid 1920's to the mid 1930's.

Carl Van Vechten's

Nigger Heaven was published

in 1926 and despite offending a number of blacks it did reveal an accurate

representation of life in Harlem; a "Negro vogue" was established

through the book's exposure of both the privileged and abject aspects of Harlem

and attracted large numbers of both the white and black erudite populations. The

buzz surrounding Harlem fueled a national market for black literature and in the

latter of 1926 Fire!!, the first solely-black produced magazine, introduced such

aspiring writers as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. There was no single

and defined style or ideology that could represent the gamut of artistic

expression of the magazine and the era, but an acute interest in the

African-American heritage, a sense of newly discovered racial pride, and the

yearning for social and political equality were fundamental to both (Lewis 27).

The magazine helped spur the over fifty volumes of poetry and fiction published

by more than 16 black writers from the mid 1920's to the mid 1930's.

--------------------------------------------------------

The diversity of the literature written

during the Harlem Renaissance truly reflected the growing interest of the

subject matter and how much needed to be said about the issues that were being

examined. The jazzy poems of Langston Hughes discussing ghetto life, the

embittered sonnets of Claude McKay assailing racism, and the ambivalent poetry

of Countee Cullen questioning where the African-American truly belonged embodied

only some of the literary discourses of blacks during the Harlem Renaissance.

Books such as Quicksand by Nella Larson and Their Eyes Were Watching

God by Zora

Neale Hurston investigated such topics as the psychological effect of the loss

of identity of black women and the impact of race and gender on the individual.

The success of black literature helped open new opportunities into the

mainstream white magazines and publishing houses, though some black leaders

denounced such capitulations as reinforcing negative African-American

stereotypes. But the writers themselves refused the validity of this attacks and

asserted that they intended to express themselves without any chains, despite

society's popular beliefs. Literature was where the Harlem Renaissance had begun

and it was where it would receive its greatest praise and recognition.

sonnets of Claude McKay assailing racism, and the ambivalent poetry

of Countee Cullen questioning where the African-American truly belonged embodied

only some of the literary discourses of blacks during the Harlem Renaissance.

Books such as Quicksand by Nella Larson and Their Eyes Were Watching

God by Zora

Neale Hurston investigated such topics as the psychological effect of the loss

of identity of black women and the impact of race and gender on the individual.

The success of black literature helped open new opportunities into the

mainstream white magazines and publishing houses, though some black leaders

denounced such capitulations as reinforcing negative African-American

stereotypes. But the writers themselves refused the validity of this attacks and

asserted that they intended to express themselves without any chains, despite

society's popular beliefs. Literature was where the Harlem Renaissance had begun

and it was where it would receive its greatest praise and recognition.

Biography and Influence of Countee Cullen

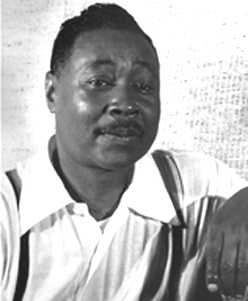

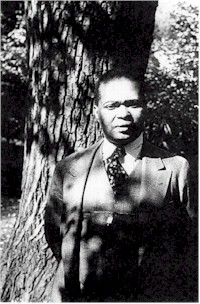

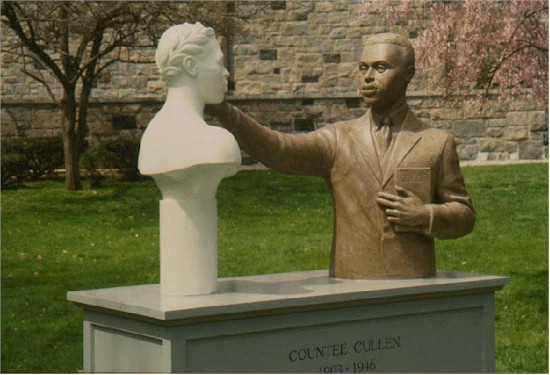

Countee Leroy Porter was not a conventional Harlem Renaissance

poet; he did not use the gaudy and cultured diction that many of his fellow

colleagues infused into their work in their effort to separate themselves from

the mundane and traditional "white poetry". Rather, Porter made use of

the time-honored poetic forms of sonnets and quatrains in his discourses about

love, beauty, and death. Though his style emulated the classic poetry of John

Keats and Percy Shelley, Countee Porter expressed the Negro experience like few

others of his day.

Countee Porter's surreptitious

demeanor, both in regard to his poetry and private life, has left many facts of

his childhood a matter of inquiry. His exact birth location remains a mystery;

though the date, May 30, 1903 is indubitable, cities ranging from New York City,

Baltimore, and Louisville, Kentucky have all been given as possible places of

his beginning. Sometime early in his childhood Porter's mother deserted him,

leaving the boy's adolescence in control of his grandmother. At nine, the two

moved to Harlem and lived in an apartment near Salem Methodist Episcopal, the

region's largest church. His grandmother soon died, and the church's head

pastor, Reverend Frederick Cullen and his wife, adopted the young man. Reverend

Cullen was a prestigious spiritual and societal leader, helping found the

National Urban League and heading the Harlem branch of the NAACP. He would use

his influence to get his adopted son enrolled at the highly acclaimed De Witt

Clinton High School in Manhattan, where Countee quickly stood out shining as one

of the few black students. Making no waste of the excellent opportunity, Countee

Cullen became a member of the honor society and was elected editor of the school

newspaper; an early poem entitled "I Have a Rendezvous With Life" was

published in the school's literary magazine and won a prize (Otfinoski 69). He

was accepted at New York University after graduating in 1922.

During his time at NYU, Cullen's

talent was fostered by his poetry's success. Soon, distinguished periodicals

such as Poetry, Harper's, and the American Mercury showcased Cullen's lyrical

brilliance. Following his graduation in 1925, Cullen gained further recognition

as the winner of Poetry magazine's esteemed John Reed Memorial Prize for the

poem "Threnody for a Brown Girl" (Shucard 56). Another famous

African-American poet, Langston Hughes, took second place in the same contest,

and the two became close friends thereafter. Hughes's poetry embodied the Harlem

Renaissance's vanguard writing style, filled with jazz and color; yet Cullen

felt that his friend's work d id not belong "to the dignified company, that

select and austere circle of high literary expressions which we call

poetry" (qtd. in Otfinoski 57). Cullen's increasing popularity in 1925

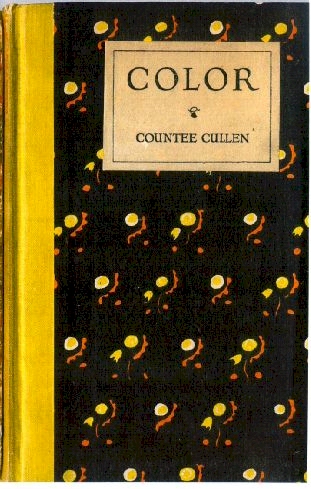

allowed for the publication of his first volume of poetry; Color was one of the

year's most lauded works and marked a momentous milestone for the Harlem

Renaissance; the movement now proved it went far beyond the reactionary

literature of a few embittered blacks and reflected the elegance with which

poets like Cullen employed a measured line and the skillful rhyme (Collier 73).

Now 23, Countee Cullen ranked as the most celebrated black poet in America. He

earned his masters degree in 1926, studying literature at Harvard before

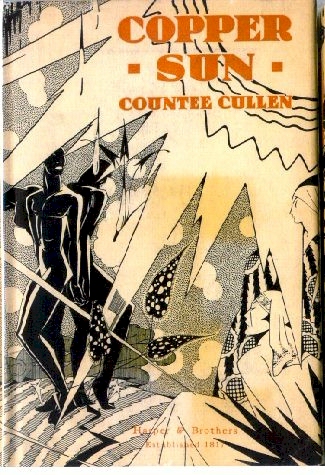

publishing The Ballad of the Brown Girl and Copper Sun in 1927, the latter of

which critics assailed for containing too few racial poems; an indicative fact

of Cullen's belief that he was not a "Negro poet", but rather a poet

who happened to be black.

id not belong "to the dignified company, that

select and austere circle of high literary expressions which we call

poetry" (qtd. in Otfinoski 57). Cullen's increasing popularity in 1925

allowed for the publication of his first volume of poetry; Color was one of the

year's most lauded works and marked a momentous milestone for the Harlem

Renaissance; the movement now proved it went far beyond the reactionary

literature of a few embittered blacks and reflected the elegance with which

poets like Cullen employed a measured line and the skillful rhyme (Collier 73).

Now 23, Countee Cullen ranked as the most celebrated black poet in America. He

earned his masters degree in 1926, studying literature at Harvard before

publishing The Ballad of the Brown Girl and Copper Sun in 1927, the latter of

which critics assailed for containing too few racial poems; an indicative fact

of Cullen's belief that he was not a "Negro poet", but rather a poet

who happened to be black.

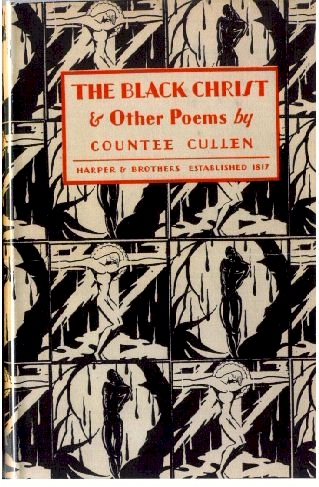

Countee's relationship with Yolande Du Bois, daughter of the famous black writer

and leader W. E. B. Du Bois, held the similar furtive theme that Cullen retained

his entire life. Their marriage, the social apex of 1928 for the Harlem

Renaissance, was not a successful one; the two divorced in less than two years.

Mirroring his private failure, Cullen's literary career began to experience

significant setbacks. His fou rth volume of poetry,

The Black

Christ and Other Poems, was published in 1929 and, as the title suggests, contained rich

religious imagery. Cullen's first and only novel, One Way to Heaven, took a deep

look at Harlem life. However, both these works were critically berated as inapt

and structurally flawed (Otfinoski 58). Cullen began a career in education,

teaching English and French at the all-black Frederick Douglass Junior High

School in Harlem, when the Great Depression left him without a steady income

based on his literary work. Though his writing greatly waned in the 1930's,

Cullen did translate the Greek tragedy Medea by Euripides and managed to publish

The Lost Zoo, a children's book about animals that refused boarding Noah's Ark.

He wedded Ida Mae Roberson, a close friend for ten years, a union that was

considerably better than his previous marriage. Cullen then adapted Arna

Bontemps's novel, God Sends Sunday, into the musical St. Louis Woman, which was

persecuted by black critics for creating a negative image of African-Americans.

Critical harangues worsened Cullen's high blood pressure and on January 9, 1946,

at age 42, he died of uremic poisoning.

rth volume of poetry,

The Black

Christ and Other Poems, was published in 1929 and, as the title suggests, contained rich

religious imagery. Cullen's first and only novel, One Way to Heaven, took a deep

look at Harlem life. However, both these works were critically berated as inapt

and structurally flawed (Otfinoski 58). Cullen began a career in education,

teaching English and French at the all-black Frederick Douglass Junior High

School in Harlem, when the Great Depression left him without a steady income

based on his literary work. Though his writing greatly waned in the 1930's,

Cullen did translate the Greek tragedy Medea by Euripides and managed to publish

The Lost Zoo, a children's book about animals that refused boarding Noah's Ark.

He wedded Ida Mae Roberson, a close friend for ten years, a union that was

considerably better than his previous marriage. Cullen then adapted Arna

Bontemps's novel, God Sends Sunday, into the musical St. Louis Woman, which was

persecuted by black critics for creating a negative image of African-Americans.

Critical harangues worsened Cullen's high blood pressure and on January 9, 1946,

at age 42, he died of uremic poisoning.

A year after Cullen's death, a volume

aptly entitled On These I Stand was published containing a selec tion of poems

the author thought to be his best. Countee Cullen's best work was achieved as a

young man, and though his classical style separated him from the other writers

of the Harlem Renaissance, it was attacked as lacking the vitality and

liberating force of contemporary black culture. Criticism of Cullen points to

his uncontrollable perfectionist form, "In a personal way, using poetry as

a device to maintain control worked for him, but for that to happen, he

frequently lapsed into over-control, sacrificing the blood of poems to

structures and language" (Shucard 124). Countee Cullen represented the

other half of the brassy Jazz age, the highly intellectual influence of the

Harlem Renaissance that inculcated the minds of 1920's and 1930's America.

tion of poems

the author thought to be his best. Countee Cullen's best work was achieved as a

young man, and though his classical style separated him from the other writers

of the Harlem Renaissance, it was attacked as lacking the vitality and

liberating force of contemporary black culture. Criticism of Cullen points to

his uncontrollable perfectionist form, "In a personal way, using poetry as

a device to maintain control worked for him, but for that to happen, he

frequently lapsed into over-control, sacrificing the blood of poems to

structures and language" (Shucard 124). Countee Cullen represented the

other half of the brassy Jazz age, the highly intellectual influence of the

Harlem Renaissance that inculcated the minds of 1920's and 1930's America.

Selected works:

Click here for a chronology of Cullen's life

Click here for Cullen's thoughts on Blacks, literary tradition, and modernity

Analysis of "Any Human to Another"

The Text:

The ills I sorrow at

Not me alone

Like an arrow

Pierce to the marrow

Through the fat

And past the bone.

Your grief and mine

Must intertwine

Like sea and river,

Be fused and mingle,

Diverse yet single,

Forever and forever.

Let no man be so proud

And confident,

To think he is allowed

A little tent

Pitched in a meadow

Of sun and and shadow

All his little own.

Joy may be shy, unique,

Friendly to a few,

Sorrow never scorned to speak

To any who

Were false or true.

Your every grief

like a blade

Shining and unsheathed

Must strike me down.

Of bitter aloes wreathed,

My sorrow must be laid

On your head like a crown.

Click here to read more of Cullen's poetry

The Analysis:

Countee Cullen's "Any Human to Another" stands distinctly apart from

many of the poetry African-Americans were writing during the Harlem Renaissance.

While it was the goal of the majority of blacks to celebrate, through

literature, their uniqueness and separation from the white culture they had been

oppressed under, Cullen's poem reaches a higher level of intellectuality by

commenting on the ubiquitous Harlem theme of pain, but through a universal

approach; he makes his point clear that what every human has to share, whether

white or black, is the sorrow he or she feels and thus can relate to through

other humans.

The poem's opening stanza runs six

lines of the same sentence and contains an unconventional rhyming scheme of

abccab. Cullen achieves his point of relating the individual's pain as part of

the overall whole, though remaining an independent being, through this broken up

sentence; each line contributes to the amalgamation of a complete sentence yet

remains distinct, standing alone on its own line; the entire poem is written using this symbolic

syntax. The opening lines introduce unspecified

"ills" of which the speaker indicates he does not feel alone. Though

the exact troubles the speaker refers to go unnamed throughout the poem, the

severity of their impact is clearly indicated through the concluding four lines

of the first stanza. The ills are "Like an arrow" (3), they

"Pierce to the marrow, / Through the fat / And past the bone" (4-6).

This simile, comparing human grief to an arrow that egregiously harms the health

of "any human", serves to prove the authenticity of the deep-seated

pain experienced particularly by blacks during the time period (Wasley 3). Of

the stanza's twenty-two words, at least six have negative connotations, each

carefully chosen. "Ills' gives a more absolute feeling of pain since it

encapsulates both mental anguish and physical agony, repercussions of the era's

racism. The placement of "alone" is indicative of the poem's theme;

the implication of the line refutes the words connotation, "Not me

alone" (2), thus though it appears in the poem, its function is to convey

its opposite; this was the precise dichotomy Cullen wished to reveal about the

era. Though human distress is a personal emotion, it commonly results from a

connection with another human, and for blacks during the Harlem Renaissance,

grief was a shared sentiment; each feeling society's prejudice separately, but

collectively embodying the epoch's ignorance. "Pierce" denotes an

almost unnoticeable type of cut, though stinging and lasting in effect. The

glamour and attraction of 1920's America makes the pervading undercurrent of

racism at times inconspicuous, but the racially bias climate of the time period

had enduringly noxious effects on the lives of African-Americans.

standing alone on its own line; the entire poem is written using this symbolic

syntax. The opening lines introduce unspecified

"ills" of which the speaker indicates he does not feel alone. Though

the exact troubles the speaker refers to go unnamed throughout the poem, the

severity of their impact is clearly indicated through the concluding four lines

of the first stanza. The ills are "Like an arrow" (3), they

"Pierce to the marrow, / Through the fat / And past the bone" (4-6).

This simile, comparing human grief to an arrow that egregiously harms the health

of "any human", serves to prove the authenticity of the deep-seated

pain experienced particularly by blacks during the time period (Wasley 3). Of

the stanza's twenty-two words, at least six have negative connotations, each

carefully chosen. "Ills' gives a more absolute feeling of pain since it

encapsulates both mental anguish and physical agony, repercussions of the era's

racism. The placement of "alone" is indicative of the poem's theme;

the implication of the line refutes the words connotation, "Not me

alone" (2), thus though it appears in the poem, its function is to convey

its opposite; this was the precise dichotomy Cullen wished to reveal about the

era. Though human distress is a personal emotion, it commonly results from a

connection with another human, and for blacks during the Harlem Renaissance,

grief was a shared sentiment; each feeling society's prejudice separately, but

collectively embodying the epoch's ignorance. "Pierce" denotes an

almost unnoticeable type of cut, though stinging and lasting in effect. The

glamour and attraction of 1920's America makes the pervading undercurrent of

racism at times inconspicuous, but the racially bias climate of the time period

had enduringly noxious effects on the lives of African-Americans.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

The poem's theme of shared grief is

extended in the second stanza's six lines, consisting again of an unusual rhyme

scheme, but one entirely different from that of the first stanza. In fact, every

stanza has at least an altered rhyme scheme of any of the others; every human

has grief (each stanza has a rhyme scheme), every human feels it in different

ways (no rhyme scheme is d oubled),

and every human's grief contributes to the world's oceans of misery (each stanza

serves as a part of the entire poem). Lines 7-12 explicitly convey the author's

feeling about the interconnectedness of human suffering, using the fitting

comparison of grief to water bodies. The speaker directly addresses the reader

when he claims "Your grief and mine / Must intertwine / Like sea and river"

(7-9); the origins of the grief are never given and may not be the same,

therefore indicating how closely related any human's grief is to another; their

sorrows "must" come together and constitute a portion of the entire world's

troubles, just like smaller, separate bodies of water come together and

concertedly empty out into a larger body of water. Cullen's personification of

grief being "fused" and "mingling" explains how grief is shared among humans,

even though each human experiences a "diverse" and "single" sorrow. Cullen

stresses the equality, particularly of blacks and whites, by combining the most

prevalent and experienced emotion of mankind: grief. The closing line of the

second stanza again stresses the absoluteness of human suffering and the

universality that the poem's title introduces, proclaiming that grief

intertwines "Forever and forever" (12). The third and fourth stanzas give a

grave warning against the sin of pride and express the inclusiveness of sorrow.

oubled),

and every human's grief contributes to the world's oceans of misery (each stanza

serves as a part of the entire poem). Lines 7-12 explicitly convey the author's

feeling about the interconnectedness of human suffering, using the fitting

comparison of grief to water bodies. The speaker directly addresses the reader

when he claims "Your grief and mine / Must intertwine / Like sea and river"

(7-9); the origins of the grief are never given and may not be the same,

therefore indicating how closely related any human's grief is to another; their

sorrows "must" come together and constitute a portion of the entire world's

troubles, just like smaller, separate bodies of water come together and

concertedly empty out into a larger body of water. Cullen's personification of

grief being "fused" and "mingling" explains how grief is shared among humans,

even though each human experiences a "diverse" and "single" sorrow. Cullen

stresses the equality, particularly of blacks and whites, by combining the most

prevalent and experienced emotion of mankind: grief. The closing line of the

second stanza again stresses the absoluteness of human suffering and the

universality that the poem's title introduces, proclaiming that grief

intertwines "Forever and forever" (12). The third and fourth stanzas give a

grave warning against the sin of pride and express the inclusiveness of sorrow.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

An element of spirituality, which is

continued later in the poem, cautions the reader against pride, one of the seven

deadly sins of Christian doctrine. The word "confident" in line 14,

typically carrying a positive connotation, is warned against as well; Cullen

uses the word, rather, to imply the "arrogance, pomposity, and

self-importance" with which society was ruled by during the gilded 1920's,

characteristics that "go against the poem's theme of equality and universal

fellowship" (Wasley 3).  The speaker then mocks any man who thinks "he is

allowed / A little tent / Pitched in a meadow / Of sun and shadow / All his

little own" (15-19). These lines convey the foolishness of isolating the self

from the undeniable connection each human shares with the world; the repetition

of the word "little" in line 16 and 19 stresses the speaker's contempt for those

who deny themselves the experience of unity and equality, scorning how small

their worlds then become. The adjectives describing "joy" in the fourth stanza

set up the stark contrast between happiness and sorrow. While joy is "shy,

unique / Friendly to a few" (20-21), sorrow ramifies into the lives of any

human, whether they be "false or true" (24); therefore, grief, contrasting to

happiness, affects all people regardless of the morality with which they live

their lives; this truth augments the power and authenticity of grief's impact on

"any human". Again, Cullen personifies sorrow as capable of scorn and speech,

creating a much bolder image of the emotion than that of the coy and less-felt

sentiment of joy.

The speaker then mocks any man who thinks "he is

allowed / A little tent / Pitched in a meadow / Of sun and shadow / All his

little own" (15-19). These lines convey the foolishness of isolating the self

from the undeniable connection each human shares with the world; the repetition

of the word "little" in line 16 and 19 stresses the speaker's contempt for those

who deny themselves the experience of unity and equality, scorning how small

their worlds then become. The adjectives describing "joy" in the fourth stanza

set up the stark contrast between happiness and sorrow. While joy is "shy,

unique / Friendly to a few" (20-21), sorrow ramifies into the lives of any

human, whether they be "false or true" (24); therefore, grief, contrasting to

happiness, affects all people regardless of the morality with which they live

their lives; this truth augments the power and authenticity of grief's impact on

"any human". Again, Cullen personifies sorrow as capable of scorn and speech,

creating a much bolder image of the emotion than that of the coy and less-felt

sentiment of joy.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The concluding stanza both continues

previous motifs of the work and also introduces new ideas that enhance the theme

and effectiveness of the poem. The speaker again addresses the reader directly

when he states that "Your every grief / like a blade / Shining and

unsheathed / Must strike me down" (25-82). Here, the word "must"

is used again, this time to signify that the speaker needs to feel the brunt of

the reader's sorrow because human suffering becomes dignified when it is

collective; though the blade will strike the speaker down, Cullen feels that

"shared grief is given a noble quality" (Wasley 4), symbolized by his

description of it as "shining and "unsheathed" (27), like a knight's sword.

Cullen, by making the line the only one not capitalized in the poem, symbolizes

the importance of the comparison of grief to a blade, both serving complex

functions of inflicting pain, yet containing a noble quality . The speaker, after accepting the reader's sorrow, demands the reader accept his

own sorrows; this mutual acceptance may be difficult, but it will allow each

person's grief to be healed, it will be a "bitter aloe" (29). The last

two lines of the poem reintroduce the religious motif of the poem; the speaker

declares that his own sorrow "must be laid / On your head like a

crown" (30-31). This religious allusion, comparing the reader to Jesus

Christ, symbolizes how important absorbing human sorrow is to spiritual growth.

In Christian belief, Christ suffered the most painful death to atone for the

sins of all humans; the crown of thorns placed on His head before his

crucifixion symbolized the king-like quality of his nature, though it resulted

in even further pain. Cullen, then, proudly proclaims that each man may serve to

be another's Christ if he or she is willing to endure the sorrow of gaining such

knowledge.

. The speaker, after accepting the reader's sorrow, demands the reader accept his

own sorrows; this mutual acceptance may be difficult, but it will allow each

person's grief to be healed, it will be a "bitter aloe" (29). The last

two lines of the poem reintroduce the religious motif of the poem; the speaker

declares that his own sorrow "must be laid / On your head like a

crown" (30-31). This religious allusion, comparing the reader to Jesus

Christ, symbolizes how important absorbing human sorrow is to spiritual growth.

In Christian belief, Christ suffered the most painful death to atone for the

sins of all humans; the crown of thorns placed on His head before his

crucifixion symbolized the king-like quality of his nature, though it resulted

in even further pain. Cullen, then, proudly proclaims that each man may serve to

be another's Christ if he or she is willing to endure the sorrow of gaining such

knowledge.

Though not representing a typical

Harlem Renaissance poem, Countee Cullen's "Any Human to Another"

establishes a greater level of unanimity and responsibility among every

individual. It addresses the racially tense climate of the era, but allows any

human, white or black, to understand and relate to its universal message of

equality.

Collier, Eugenia W. "I Do

Not Marvel, Countee Cullen." Modern Black Poets: A Collection of

Critical essays. Ed. Donald B. Gibson. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc.

1973. 69-83.

Countee Cullen (1903-1946). Ed. Walter C. Daniel. 18 January 2003.

http://www.georgetown.edu/faculty/bassr/heath/syllabuild/iguide/cullen.html

Lewis, David Levering. When Harlem Was in Vogue. New York: Vintage Books, 1982.

Otfinoski, Steven. American Profiles: Great Black Writers. New York: Facts on

File, Inc., 1994.

Shucard, Alan R. Countee Cullen. Boston: Twayne, 1984.

"The Harlem Renaissance". 18 January 2003. http://www.unc.edu/courses/eng81br1/harlem.html

Wasley, Aidan. "Any Human to Another". Poetry For Students: Presenting Analysis,

Context,

and Criticism on Commonly Studied Poetry. Ed. Marie Rose Napierkowski. Detriot,

MI:Gale

Research. 1998. 2-5.